A New Year for Old Books

The widow came by three times last summer. It was always on a Wednesday afternoon when we were slow. For some reason, I was the one working in the store. Sydney was out with our daughter Sally Jane, grocery shopping or going for ice cream. When July and August roll around in Washington County, and the smothering humidity brings swarms of insects that surround all parts of your face, going for ice cream is all one can do for fun. Anyway, the first time I met this widow (let's call her Dolores just because you don't hear that name enough these days), she sped up the driveway of our house in a boxy bright green SUV and tore up some of the grass in front of the store. She wasn't drunk. Dolores was in a hurry.

Before I could get her attention, waving my arms as I ran out the screen door of the bookstore to alert her that our driveway was not the store parking lot, she had thrown her green machine in park, hopped out, and begun to walk back to open her trunk, all the while yelling at her little white miniature poodle for barking at me as I approached. Though it was clear she had a lot on her mind, she moved with a forceful sense of purpose.

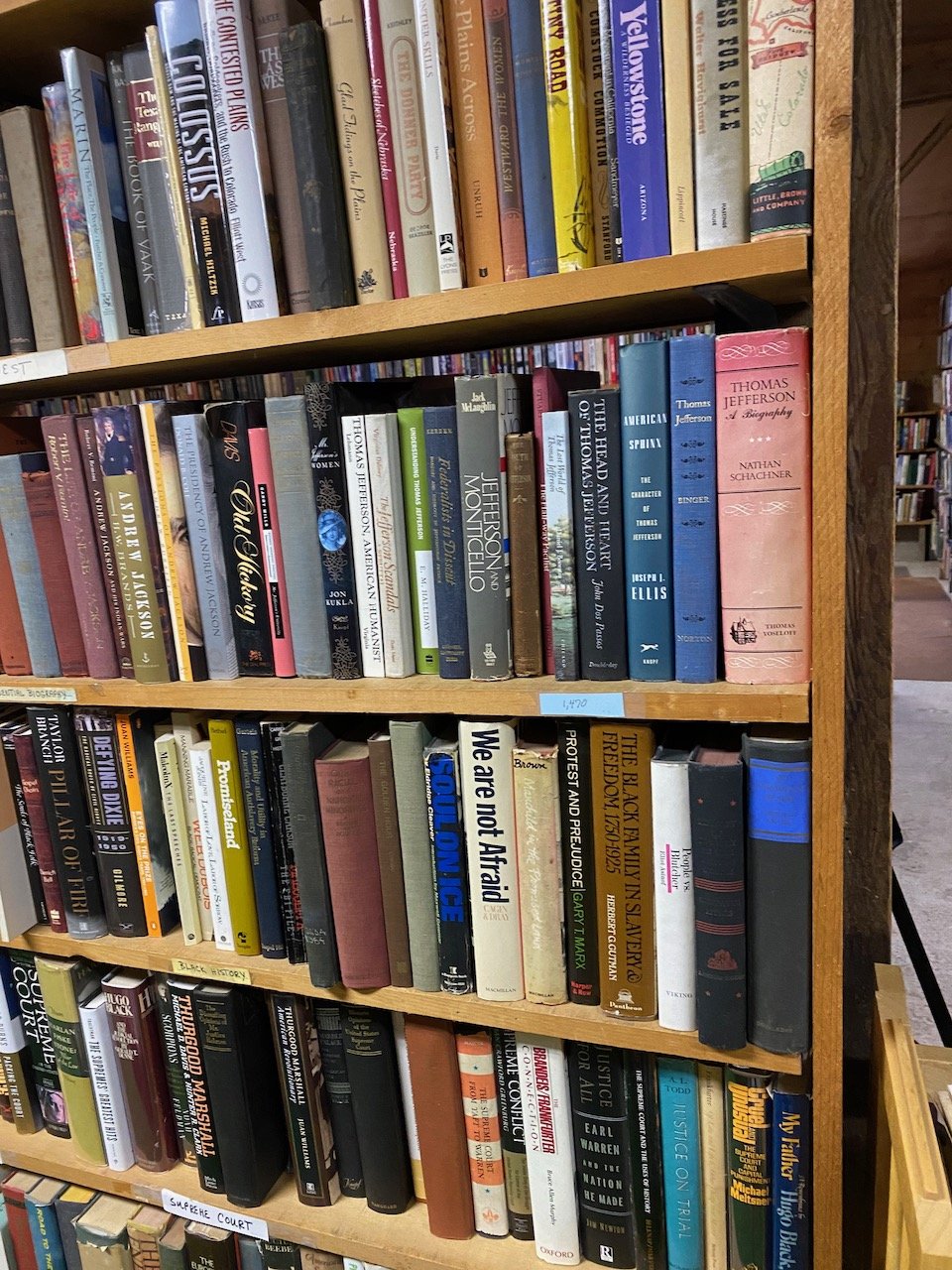

It occurred to me that she was the woman I had spoken to on the phone earlier that morning, the one who said she had some books for me. She had three small, open cardboard boxes. I eyed a few of the books on top. Most of the titles were about fishing and hiking in the Adirondacks. My anxiety had started to set in. I mostly rang people up and carried boxes. Book buying wasn't my area of focus. That was left to Sydney. Of the two of us, she was under the tutelage of the previous owner, Edie Brown, who advised her on what to buy from casual booksellers who ventured up our dirt road. I did overhear Edie telling Sydney once that we should always take books about local or regional history and mountaineering. "This stuff always sells," Edie said, holding up a dusty leather-bound volume about the history of Saratoga Springs.

So I assumed I'd be taking many of Dolores's books. But how much cash to offer her was my problem. What are these old books worth? How am I to know? I'm not going to look up each one on the internet only to find each is selling for seventy-five cents a piece on Amazon. After carrying all the boxes into the store, which is my primary job in our Owl Pen operation, I sat down to look through each box. Dolores stood in one spot by the door with her yipping little dog. She turned her head slowly, surveying the store, getting her bearings. Barely acknowledging her dog's bark, she seemed in a daze.

"My, you sure have a lot of books here," she said.

"Yes. They came with the place," I said as I pulled out one book on camping after another, increasingly worrying about what I should take and how much they should all add up to in the end. I didn't want to lowball this kind albeit distracted lady and insult her.

"So, are you enjoying up here? I read about you guys in the paper. You came all the way from California?"

"Yep."

"Why I on earth would you do that?" she said with a crazed smile, staring off into the dust hanging in the sunlight that shone through the barn windows.

I launched into the standard explanation that Sydney, and I are still fine-tuning to this day—something about the property, the increasing heat index in LA, the pandemic, our finances, and our quality of life. Dolores nodded. After an awkward beat, I couldn't help but cut to the chase, if only to get the stress-inducing business of book buying out of the way.

"Just so you know, I can't take all of these books from you. We only buy what we need."

"What? Oh, no, no. I'm just here to donate these books. I need to get rid of them."

"Really?" I said. I sighed quietly in relief, looking down at the sizable number of sellable products in the boxes before me on the floor. "This is quite the donation."

"Well, if you like that, there's plenty more where that came from!"

Dolores's dog began barking again. This time it didn't stop; the yipping and yapping continued all the way out to the car. I walked with her, carrying the empty boxes that had held her books, making sure to thank her a few times so she knew I was genuinely grateful for her contribution to my new livelihood. Dolores explained how her husband of forty years or so had died just ten days before. He had keeled over while they were on a walk in the neighborhood with the dog, the same dog that had been annoying me since she'd arrived. The man had just collapsed from a heart attack right there in the twilight hour on the empty village street under the greening trees amidst the burgeoning bloom of spring.

I expressed my condolences. A moment passed, a moment filled with nothing but the repetitive yelp of the dog, now aware of the squirrels and birds, choking itself on the leash held in Dolores's unsteady hand. I had a thought.

"Wait, your husband passed away last week, and you're here bringing me his books?"

"Well, there are so many, and it's really just too much clutter. Besides, what am I going to do with them?"

People often ask where we get our books and how we keep our inventory stocked. My answer always seems harsh, but it is honest and unadulterated.

"Dead people." That's what I tell them. Sydney finds this cringeworthy. She gets embarrassed when she hears me say it, but she would never deny that it is true. Owl Pen Books stocks its shelves with the literary possessions of the deceased. There you have it. Our dark secret revealed.

Initially, I found the reality of the business, or at least this aspect, a bit morbid. And if I were to think too long about it, it would be depressing. As time goes on, however, I'm learning to accept the practice and find an inherent value in it. The easy mistake is to see our used bookstore business model as something akin to recycling. After all, books are not aluminum cans, Styrofoam cups, or plastic forks. We won't be burning them for fuel. (Although some out-of-date encyclopedia sets and Time Life collections might eventually make their way into our wood stove to make room on our dusty back stockroom shelves.)

Usually, someone passes, someone wealthy enough to have a room devoted solely to displaying books—a study, or a small library. And if they have next of kin, the readers or literary devotees of the family scour the shelves and boxes for rare and collectible editions or sentimental items they will probably place on a shelf in their home or a cardboard box in their basement, never to be read again. Then there is an estate sale we hear very little about. Collector types and online sellers might comb through the remaining books looking for scarcely found first editions or whatever they think they can get a pretty penny for. A few days after, we receive a call from someone, a family member, or a realtor, asking if we'd like to come take a few hundred books, sometimes a thousand or so. But in situations like these, I personally can't leave anything behind for them to throw in the trash. I'd rather throw the books in my trash bin and spare them the hassle of getting the local library to take them. It's the least we can do for those contributing considerably to this historic sixty-year-old business.

For most of her life, my mother was an avid reader, mostly of crime novels or the occasional Oprah's Book Club pick. She regularly checked out stacks of them from the library. When I was a kid, she finished a book every few days. But any unfamiliar person who entered our house would have no idea my mom was such a voracious reader. There were no bookshelves or decorative bound editions anywhere, not even a coffee table book in the living room. I recall two or three cookbooks in a cabinet in the kitchen. Other than that, there was the small tower of library-stamped hardcover mysteries with plastic jackets on her nightstand. To my mom, novel-length stories were a great way to relax and escape the daily grind, but books, the physical objects themselves, were just clutter, one more thing to collect dust.

When my mother sold the old house to move out east on the north fork of Long Island, her habit of frequenting the local library did not stop. The townhouse she shared with her second husband was free of shelves displaying the reading she had accomplished over the years, just the same pile under the lamplight next to her bed.

Eight years ago, my mother's husband died suddenly in the late spring. Shortly after the funeral, I went to visit her for a few weeks. What I expected to be many days of unpredictable bursts of tears and conversations bookended with fits of uncontrollable sobs turned out to be quite different. My mother seemed obsessed with removing all the clutter from her house.

Her late husband sold small antiques and collectible items he found at garage and estate sales on eBay. It was a hobby turned business he started years into his retirement. We never liked each other and had very little in common, but when he started getting into that world, I became more interested in what he had to say at the dinner table whenever I visited. One time he found a four-string tenor banjo at a garage sale in a nearby town, and it was worth thousands of dollars, enough to fund a vacation to Bermuda for him and my mother. It was like a front-row seat to a personal episode of Antiques Roadshow.

But now, all of it had to go. The rusty promotional signs for long-forgotten products, the vintage children's toys from the 50s in boxes, the World's Fair posters and guidebooks, and all of the rare knick-knacks and paraphernalia needed to be removed from the garage and attic. Boxes of "junk," as my mother referred to it, needed to be tossed or donated to Goodwill. She certainly wasn't going to be selling it online. It was all clutter. While I was going up and down the fold-out ladder to the attic, my mother shouted, "While you're up there, grab the boxes with your old report cards and sports trophies, we can throw those out too!" I ducked my head down into the garage to meet her eyes and send a disapproving look to signal that I barely thought this purging of her late husband's possessions so soon after his death was a healthy way of coping with her loss. I certainly wasn't about to let her destroy old memories of me, her son, just because a few boxes in the attic were taking up space and collecting dust. She responded, "What? You can keep what you want. I'll put it all in one box and mail it to you." And that is what she did. People do strange and drastic things when in the throes of grief.

Dolores reminded me of my mother. She even seemed around the same age. But what was most strikingly familiar to me was the tightly strung pace at which she moved, as if she had five more stops to make that day to unload all her husband's possessions. When she mentioned a whole room full of books she'd like to be rid of, I offered to come to pick them up, figuring that each trip up the winding country roads from the village would be another hassle for a widow in mourning. She politely declined, saying that she liked getting out of the house. Then she tried to sell me some cross between a kayak and a catamaran her husband had bought and used once years ago on Lake George. The annoyance I detected in her voice was the same I had felt in my mother as if she was pissed at her late-life partner for burdening her with the task of clearing out all of this "junk" from the garage. After looking up this lake boat contraption on my phone, I told her thanks but no thanks. The widow then hurried to get in her car and drive out of our parking lot down the dirt road round the bend, seeming to disappear through the woods.

Dolores returned two more times that summer, on each occasion bringing a few boxes of books we could use; each time she came with the dog. As promised, she brought at least two filled with nothing but books on canoeing. We gave her store credit, and she went to pick out one or two mystery novels, but you could tell she didn't want any more stacks accumulating in her house or to refill the shelves she'd been emptying.

Books are living objects. Yes, they collect dust. We have many dusty old ones in our store inventory. But each has had a moment spent with a person, some brief and some for entire lifetimes. Some need to be updated but serve as historical artifacts, which you might not find at your local library and certainly not at a Barnes and Noble. Often, they are reminders of personal milestones, careers, hobbies, interests, and accomplishments. (One day, I'd like to read all of War and Peace and leave it on a shelf until I die as a kind of trophy I could glance up at to instill pride or show off as an achievement to vain friends.) But when the person passes on, these beloved books become reminders of those who are no longer there. Eventually, they become just another item needing to be removed so the house can be sold. We give these books a second, third, or fourth life at Owl Pen Books. We often receive them with the previous owner Edie Brown's penciled-in price on the inside cover. Sometimes we receive small collections with a book or two bought from the original owner, Barbara Probst. What initially seemed like something oddly funny, a sign of our unconventional business model, has become a point of pride. Our store does more than sell books and records out of a barn that once housed chickens. It gives new lives and homes to works that people from our past, many long deceased, have spent considerable effort and time, sometimes lifetimes, to create. Yes, we get our books from dead people, but at Owl Pen Books, we proudly provide clutter for each new generation.

*If 2022 wasn't a year you'd like to remember, if many of the moments are just standing in the way of better times long ago, don't let them collect dust in your memory. Put them aside or trade them in for better ones in this new year. We know this can be challenging. But if we can give a new life to a two-hundred-page guide to the butter and cheese factories of the Northeastern United States published at the turn of the century—yes, we actually sold that book last year—we at Owl Pen Books believe you can breathe in vitality by letting the past die its natural death, to give birth to a more promising future. We hope you take action to enlighten yourself, to gain a fresh perspective by clearing those literal and figurative shelves, making room for knowledge and/or serenity, the kind of things found in a good old book—or a stack of them.

Best wishes for a happy 2023!